rancho arroyo grande

2021 - 2022

Rancho Arroyo grande (RAG) is approximately 4,000 acres of land, about twelve miles inland from the coast and approximately eight miles northeast of the city of Arroyo Grande, in San Luis Obispo County, California, neighboring Lopez Lake and the Los Padres National Forest. The ranch is nestled in the beginnings of the southern hills of the Sierra Madre Mountains—Central California’s coastal mountain range. RAG is one among many “ranchos” throughout California named and controlled by early Spanish “rancheros” and missionaries who occupied the land the Chumash people lived and cared for dating back 10,000 years ago. The chumash of this region call themselves the Stishni and spoke a language very distinct to the region. After Mexico gained independence from Spain around 1821, California was secularized and the Chumash people became indentured. In 1841, the Mexican government granted RAG to a Mexican soldier, Zeferino Carlon, who sold it to his daughter and new son in law, Frances Branch in 1850. In spite of the cession of California to the United States following the U.S.-Mexico War, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ensured that the earlier land grants would be honored.

With almost three hundred acres of vineyards, RAG is purported to have grown the grapes that cultivated the first U.S.-branded wine in 1871. Over the last twenty-five years, RAG has undergone significant development by landowners who lived on the property and built housing, an equestrian center, horticulture center, and artist studio. Over 3000 acres remain undeveloped and currently home to bears, invasive feral pigs, bobcats, mountain lions, and deer. RAG’s current owners had been open to exercising a native ecological model for restoring and stewarding the land after mass areas of vegetation and vineyards had been destroyed by the pigs, creating an opportunity for untune to aid in restoring the damaged land.

despite the converted landscape, I believe that the land’s native roots (occupied by RAG) owes much of its ecological biodiversity to the Chumash people - the rightful caretakers whose connections to the land, water, and culture the current landowners continue to benefit from.

these junior feral pigs were caught in a pig brig trapping system that was developed by Dr Anthony DeNicola (meant to be the most effective and humane trapping system currently available). These trapped pigs were shot and taken by one of the employees to be eaten by his family (not wasted), but it was still heart drenching sad, even after witnessing the destruction they caused to the land. The only justification I could add is that these animals are symptoms of settler colonialism as their history indicates. According to the book: Invasive Wild Pigs in North America - Ecology, Impacts, and Management, Russian wild boar were introduced in Monterey County in the 1920s for sport hunting. Russian wild boar and domestic swine belong to the same species, Sus scrofa, and are able to interbreed without restriction. feral pigs in California today are descendants of both the released domestic pigs and the Russian wild boar. Introductions of the Sus scrofa were both intentional like the eurasian wild boar (released as a new pig game species) and accidental like escaped domestic pigs that went wild or feral (pg 7). at the very same time, how can we justify the killing of these animals, while not the colonizers who brought them? Could choosing superiority or allowance of one species to exist over another also be a reflection of white supremacy?

In 2021, after critical habitat had been destroyed leaving bare soil around RAG’s building structures and further threatening the land impacted by the previous landowner’s neglect and by anthropogenic climate change (symptoms of settler colonialism), untune was asked to assess the degraded areas and come up with possible ways to aid in restoration that would be resilient to further pig damage and climate change (of course we know that one impacts the other).

As untune had no prior experience with feral pigs—their behavior, ecological impacts, diet, or history (aside from being introduced by European settlers), nor any experience in land restoration in that area (an area rich in biodiversity due to its unique microclimate position, but one surrounded by a prominent redneck culture that prized guns and self-sustainability)—much of the work was research, beginnings, and a very intimate learning experience that i am deeply grateful for. However, the culture did play a vital role to how much we were able to restore and steward and this remains thus far my biggest lesson on the prominence of colonial force. Still, this remained my greatest hands-on education for 3 years as I observed the soil becoming more enriched and nurtured from the native seeds I had sown and the abundant return of native animals enjoying the habitat. What I didn’t realize was how attached I had become to the plants, pollinators, frogs, and birds and the heartbreak that followed when the project came to an abrupt end. I have deep remorse for abandoning the small animals and land that I had taken on the responsibility to care for. This is my incomparable and minuscule window in which I began to understand trauma caused by loss of “home” that the indigenous people continue to endure.

the first phase of the project is explained in the following images. I’m sharing quite a bit of details (including failures). untune is always open to feedback as this is a journey of unlearning and learning dedicated to the practice of building community with those interested in interweaving culture, dwelling, and native ecology.

Rooting, vegetation loss, and bare soil caused by feral pigs is depicted in these next few photos. One thing I recognized right away was that the "vegetation" that experienced the most rooting was the non-native highly irrigated grasses such as the despised Bermuda grass. During my walks around the less human-altered acres of the land, the native shrubs and plants were left untouched

The feral pigs impact ecosystems through their rooting (seen in this photo), wallowing, foraging, and hunting. They are highly competitive for food resources such as water. Even deer are known to vacate the area.

The land around the main living structure was quite heavily rooted and became the area where I created test plots (small circular models) and as those were destroyed by the pigs, I created 2 larger circular areas that the land maintenance employees (Lupe and Michael Lopez) fenced off to protect the area until plant restoration was at a matured state

The feral pig's rooting behavior overturns and tills the soil, uprooting plants, exposing bare soil, and creating opportunities for weeds to invade. They disturb native and naturalized vegetation and reduce available forage for livestock and other animals. Their wallowing disturbs springs and streams. Their rooting and wallowing behavior also disturbs riparian areas and reduces habitat suitability for native and endangered species

Feral pigs like to rest and nest in areas with low growing dense vegetation (like neatly manicured lawns). Like most other vertebrates, feral pigs need water. Additionally, since they do not have sweat glands, in hot weather they wallow in seeps and springs to cool themselves.

Feral Pigs (evidenced here by paw prints) head for the wet Bermuda grass. Underneath the grass lies grubs—much liked treats for the pigs. Aside from roots, bulbs, and grubs, pigs show a strong preference for hard mast crops (e.g., acorns). Acorns unfortunately are a primary source of their diet. One study found that high density populations of feral pigs led to lower acorn survival and a reduced regeneration of oak trees in California

This is a drawing of Test Plot Circle #1: Seeds include Blue-eyed grass (BEG), Clustered Field Sedge (CFS), Diego Bent Grass (DBG), Deer grass (DG), Bull Clover (BC), Desert Dandelion (DD), and California Buckwheat (CB)

Circle #1 was the first test plot I attempted. The idea was to grow native grasses (local to the area) that had extremely low water needs to see if they would be less desired by the thirsty feral pigs.

5/22/22: Circle #1 remains untouched due to chicken wire fencing, however this wouldn't last long as the weather became warmer and the moist soil full of grubs attracted desperate pigs. The sown seeds do require watering until established so the soil here had been irrigated (unless it had rained)

This is a drawing of Test Plot Circle #2: Seeds include Creeping Red Fescue (CRF), Common Yarrow (CY), Diego Bent Grass (DBG), CA Buckwheat (CB)

Test Plot Circle #2 didn't last long. The pigs destroyed the area while I was gone. Because I live in Los Angeles, I was only able to come out to RAG once or twice a month. And unfortunately the land owners did not live there and only visited maybe once/month. This left a large gap in connecting to and caring for the land, a gap that was quickly filled by fast populating families of pigs

Test Plot Circle #2 - destroyed by the feral pigs

This is a drawing of test plot circle #3. Seeds include California Buckwheat (CB), Purple Needlegrass (PNG), Desert Dandelion (DD), and Deergrass (DG)

Test Plot Circle #3 - this one ended up becoming part of the larger circle #4

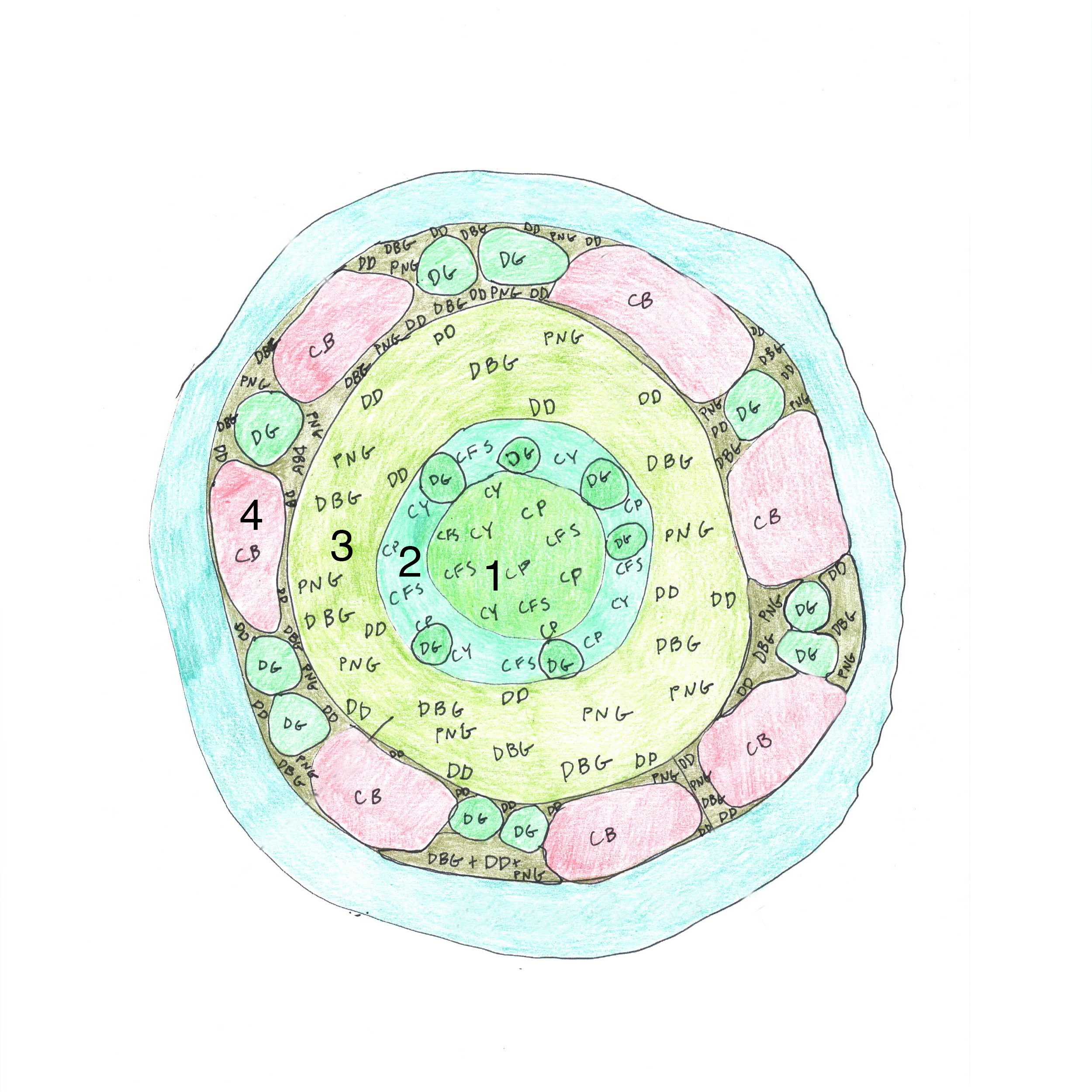

This is a drawing of Circle #4: 100 foot circumference fenced off circle at RAG that untune started in April 2022 - this was after the initial 3 test plots had failed due to pig interference and no proper fencing (before the seeds had been fully established) Sown seeds include: (1): Common Yarrow (CY), California Poppy (CP), Clustered Field Sedge (CFS), and Native Hedgerow mix (2): Deergrass (DG), Common Yarrow + Clustered Field Sedge + CA poppy (CY + CFS + CP) (3): Desert Dandelion (DD), Diego Bent Grass (DBG), and Purple Needlegrass (PNG) (4): Deergrass (DG), California Buckwheat (CB), Diego Bent Grass + Purple Needlegrass + Desert Dandelion (DBG + PNG + DBG)

Trenches were created to help collect water when it rained and alleviate soil erosion allowing the seedlings to get established. Later the trenches became the areas where we installed and tested drip hose irrigation systems that partially worked and mostly failed

And all done by hand, not machines - certainly took a lot of muscle strength

Circle #4: The idea with sowing mainly native grasses and ground cover (common yarrow and CA wildflowers) was to provide native grass alternatives that are drought tolerant (very low water-needs). The vision was for a meadow grassland that would have significant ecosystem restoration benefits, providing for native habitat, especially pollinators, and also provide the dogs an open area they could run across. At this phase the CA buckwheat around the perimeter of the circle was a test as I noticed that the buckwheat and other native shrubs around the less manicured land were not touched by the pigs.

Circle #5: This ended up being slightly smaller than Circle #4 and had a bit less built soil with the bedrock closer to the surface contributing to slower productivity than Circle #4. Seeds sown: (1): Common Yarrow + CA Poppy + Blue Flax (CY + CP + BF) (2): Purple Needlegrass + Diego Bent Grass + Clustered Field Sedge + Common Yarrow (PNG + DBG + CFS + CY) (3): California Buckwheat + Deergrass (CB + DG) and PNG-DBG-CFS-CY mix

Circle #5: untune eventually decided to use this circle as an experimental area and a way to test out certain seeds. The plan was that when it came to removing the fencing, we would first remove the fence on this one (after the area was restored and plants had been established)

Left is Circle #4 (seeds were sown April 2022) and to the right is Circle #5 (seeds were sown May 2022). This photo was taken late summer 2022 and shows a much more productive Circle #4.

Photo taken from the opposite direction (Summer 2022): Circle #5 on left, Circle #4 on the right

Heterotheca Grandiflora (Telegraph Plant) - a native referred to as a pioneer species, brought by wind or birds. I got excited to find them appearing as they are quite useful restoration plants and had risen up to action all on their own (-:

Good ole' Eschscholzia californica (California Poppies). The first of the seeds to sprout with hope and a promise of revival for the land

Achillea Millefolium (Common Yarrow). I found the yarrow to be one of the fastest, easiest growing ground covers and low moisture alternative to the the non-native lawn that existed here before. Also the white flowers attract pollinators (bees, birds, and butterflies) and beneficial insects while repelling pests. And because they spread by rhizomes, they are excellent for large open areas.

Helga removing weeds and Bermuda grass, part of the regular maintenance of creating space for native plants.

During this first year, changes were slow but steady and though not apparent in this photo, there were a lot of small animal visitors that provided me with feedback and what adjustments I needed to make in terms of water needs. Maiden clovers (native) came up on their own most likely due to the disturbed habitat - their nitrogen fixing properties were definitely needed. However other non-native clovers appeared as well and were taking over. As the soil began to restore form, I began a grueling process of removing the non-native clovers and sowing native seeds to replace them.

Close up of the flowering Common Yarrow